- The charity evaluator GiveWell increased their rating of the cost-effectiveness of GiveDirectly’s Cash for Poverty Relief program by 3-4x after reevaluating our work, including assessing new evidence.

- This update was driven by new estimates of direct cash’s positive impact on local economies, consumption, and child mortality, which show our work (past & present) is more impactful than they’d previously assumed.

- This update hasn’t changed GiveWell’s top charity and funding recommendations, but this could shift in the future.

- We’re excited about this update and look forward to continued conversations with GiveWell, as we continue to generate new evidence on cash’s long-term impact which may shift their assumptions again.

For those unfamiliar, GiveWell is a charity evaluator dedicated to finding outstanding giving opportunities by carefully assessing evidence to help donors decide where to give.

GiveWell funds charities that they believe save or improve lives most cost-effectively. They do this by assigning ‘moral weights’ to specific outcomes based on the subjective judgments from staff, donors, and beneficiaries, and then review existing research on which interventions (malaria nets, deworming, direct cash, etc.) best improve those outcomes per dollar donated. Their assessments are among the most thoughtful and comprehensive you’ll find (for more, see Appendix).

Thousands of our donors were first convinced to give directly after reading GiveWell’s evaluation of our cash transfer work, resulting in life-changing cash reaching hundreds of thousands more people in poverty than would have otherwise. They have not directed funds to our work since 2015 but use our program as a benchmark to assess the impact of other charities.

GiveWell more than tripled their estimate of GiveDirectly’s cost-effectiveness

Today, GiveWell announced they “now estimate that GiveDirectly’s flagship cash program is 3 to 4 times more cost-effective than we’d previously estimated” as a “result of re-evaluating the evidence underpinning GiveDirectly’s program, which we hadn’t formally done since 2019,” adding “this won’t alter our Top Charities list or our grantmaking.”

This increase is not due to a change in how GiveDirectly delivers your donations or the impact of cash (past & present). Rather, GiveWell now has a fuller picture of our impact after factoring in additional evidence.

We’ll focus on the pieces of data that increased (🔼) their assessment of cash below.

- Each “📈 Research finds” section is GiveDirectly’s summary of the evidence.

- All GiveWell quotations below are from their full re-evaluation and blog.

- Click ➕ to expand the sections below to learn more.

1) Spillovers: direct cash benefits recipients and their neighbors too

📈 Research finds direct cash can grow the local economy by 2.5x what is given

- Two dozen studies have documented that giving people in poverty cash can grow local economies, benefiting people in poverty who didn’t receive cash aid (“positive spillovers”). Because the money is spent in the community, it supports local small business owners like Mugabo in Rwanda →

- A robust study from Egger et al. (2022)1 of Kenyans who received GiveDirectly cash in 2015 estimated a 2.5x multiplier – for every $1,000 transfer, $2,500 in local economic activity was created – without causing an offsetting inflation in prices.2 Here’s more on the study →

⏫ GiveWell previously did not evaluate this 2.5x multiplier study, and incorporating it has a very significant effect

- GiveWell assessed the 2.5x multiplier study: “Cash transfers have significant spillover benefits to other people in their geographic area, including non-recipients and other recipients, in the treated village and in nearby villages too… We estimate that recipient consumption returns explain ~30% of a 2.5x economic multiplier, implying ~70% of the multiplier comes from non-recipient consumption gains… Previously, we had a -5% adjustment for consumption spillovers to non-recipients – i.e. we assumed non-recipients would be made slightly worse-off by not receiving a transfer.”

- These results alone drove almost half the 3-4x increase to GiveWell’s cost-effectiveness estimate.

🔽 They now incorporate it, but discount it by half due to their uncertainty in the results

- GiveWell says both of their discounts are highly subjective: ”The ultimate adjustment we settle on is highly subjective, and we think reasonable people could place more or less weight on the Egger et al. estimate.”

- They discount the 2.5x study by 40% because of uncertainty in the result: ”We don’t think we should put all our weight on Egger et al. for several reasons: [1] The multipliers have large standard errors… [2] The paper doesn’t observe net imports… [3] The paper can’t observe ambient effects across the study area… [4] We don’t think it completely supersedes previous studies… [5] the multiplier seems surprisingly large. Our best guess is to apply a 60% internal validity adjustment (i.e. a -40% downweight) to the Egger et al. spillover results.“

- They discount this 2.5x study by another 20-30% because they believe it doesn’t replicate fully in other places where we work: ”Our best guess is that spillovers to non-recipients are likely to be smaller (but still positive) under more saturated program designs and in poorer and more remote contexts… We apply an 80% external validity adjustment in Kenya (i.e. a -20% downweight) to account for this, and slightly steeper 70-75% adjustments in Malawi/Mozambique/Rwanda/Uganda.“

-

- Notably, new work from the authors of the 2.5x study predicts the opposite: “multipliers will be larger in more remote contexts… [and] real economic multipliers remain fairly constant as the size of the cash injection scales,“ which GiveWell reviewed and concluded “we find the arguments in favor of expecting smaller spillovers under more saturated programs in more remote contexts more convincing.“

2) Long-term impact: a one-time cash transfer reduces poverty for years

📈 Research finds recipients are less poor (consume more) years after a GiveDirectly cash transfer

- Consumption, a widely-accepted measure for determining poverty level, measures the total amount of goods and services consumed by individuals or households over a specific period.

- There are very few long-term (3+ years on) studies of any poverty interventions, but cash has more than any other. This limited literature finds the consumption impacts of cash diminish but do not dissipate in the long-term, with measurable positive impact even 12 years later.3

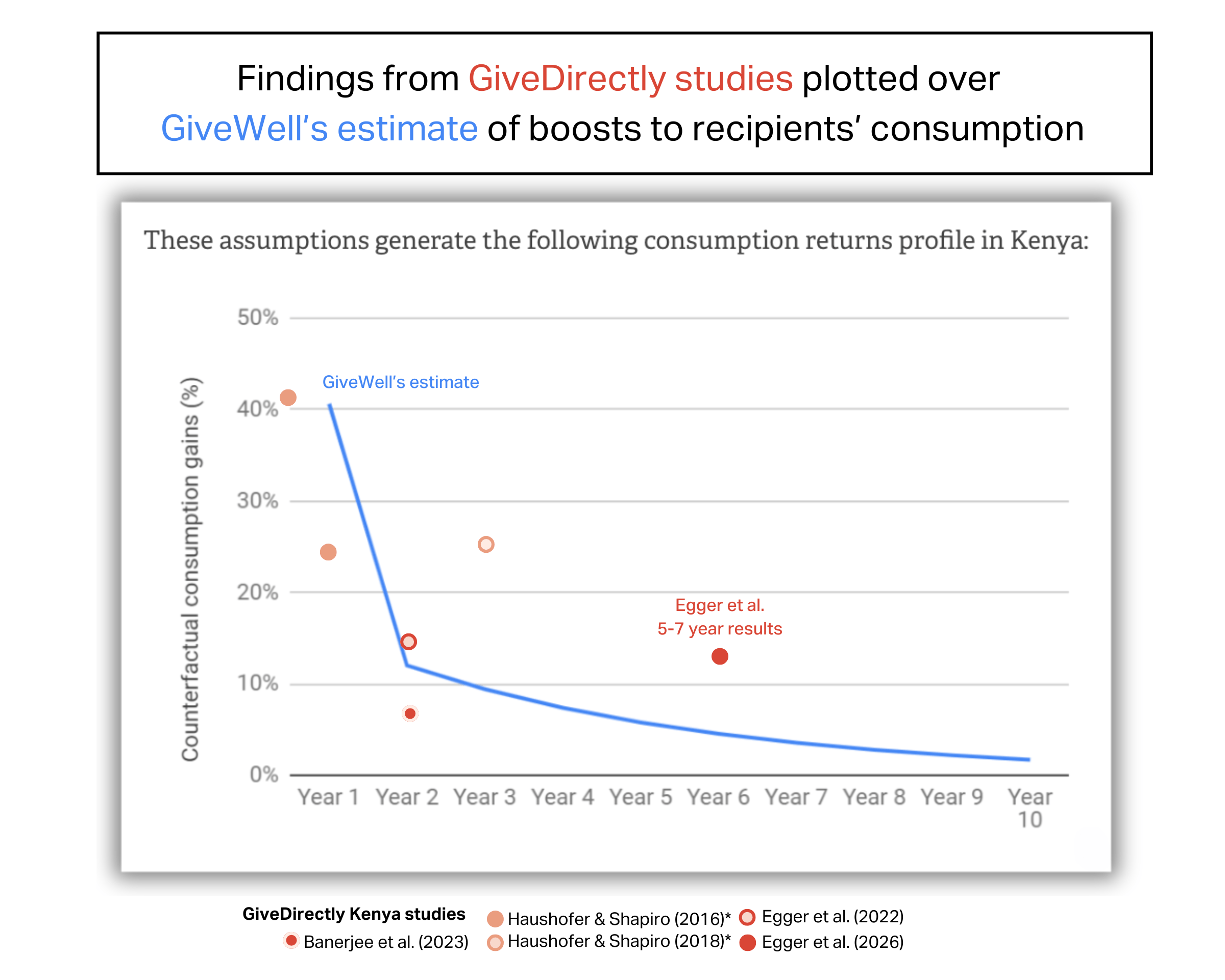

- GiveDirectly’s longest run published studies measure impacts <3 years later, including in the Egger et al. study which found ~2 years after receiving cash, families were spending 13% more than the control group. Unpublished data from the same study has found 5-7 years later these families are still spending 12% more.

🔼 GiveWell increased their estimate of how long consumption improvements last

- After consulting the evidence above, GiveWell determined, “recipients see large gains in consumption immediately after receiving the transfer, as they spend just over half (~60%) of the transfer in the first year. We expect consumption gains to persist for 10 years, but to fade out after this initial spike, as recipients spend down the rest of the transfer and the increase in local economic activity starts to fizzle out.”

- This is a more sustained increase than they’d previously assumed: “the direct consumption benefits of these transfers for recipients persisted more strongly than our original model predicted, further increasing our estimate of the impact of GiveDirectly’s cash transfers.”

- They reviewed evidence of impacts 5-7 years later that is higher than they’re predicting now, but did not weigh it heavily: “Our main uncertainty stems from preliminary results we’ve been sent from a long-run follow-up to Egger et al (2022)… [showing] 5-7 years later, recipient households had 12% higher consumption compared to households in distant control villages – almost the same difference as at the 2 year follow-up. We don’t put much weight on these results because they haven’t been subjected to external scrutiny, and seem generally inconsistent with other experimental findings. However, if these results make it through academic peer review, we would probably update towards them.” More how these results could increase their assessment here →

🔼 GiveWell also concluded that GiveDirectly recipients are poorer than they’d previously assumed

- GiveWell says their “previous model assumed that baseline consumption in Malawi, Mozambique, Rwanda and Uganda was similar to consumption levels we had calculated in Kenya. Now, we believe that consumption in those newer locations is lower than Kenya.”

- They assess that the poorer the recipient, the more good the cash does: “we think a $1,000 annual consumption gain for someone consuming $1,000 worth of goods and services a year is more valuable than a $1,000 gain for someone consuming $2,000 worth a year. This means it matters how poor we think recipients are before they receive cash transfers.”

- Because we delivered cash in these poorer contexts our Poverty Relief “program looks more cost-effective because the average recipient of GiveDirectly’s program is poorer than our previous estimate, which only assessed consumption in Kenya.”

3️) Lives saved: direct cash means fewer children die prematurely

📈 Research finds direct cash can drop infant and child mortality by half

- Researchers estimate through a process called meta-analysis that providing large cash transfers led to significant reductions in mortality among children under 5 years of age (14%) and women (30%).

- This aligns with research on GiveDirectly’s work: a published study of our work in Rwanda found a 70% drop in mortality for children under 5 and an unpublished Egger et al. follow-up found a 46% drop for Kenyan children under 5.

- These are remarkable results, as our Poverty Relief program isn’t targeted to families with children under 5, but rather gives cash to every household in a poor village. And still, it is reducing child mortality per family at rates comparable to giving out antimalarial medicines or routine vaccines. We’re currently exploring a modified version of our program that would maximize reductions in child mortality per dollar spent by giving cash to recipients most at risk of losing a child to preventable causes.

🔼 GiveWell thinks these results are ‘surprisingly large,’ and they don’t have much impact under their model

- They assess that GiveDirectly work, “leads to a 23% reduction in the risk of all-cause under 5 mortality. This is based on published results of [studies of GiveDirectly’s programs], which imply large reductions in all-cause under 5 mortality.”

- They heavily discount this evidence because of uncertainty: “We apply steep discounts to these results because they seem much more than the mortality effects estimated from a meta-analysis of government cash transfer programs, and because we don’t have a clear theoretical understanding of how effects could be this large…” Egger et al.’s working paper, due out next year, will provide more insight on the mechanisms that created this large impact.

- For GiveWell “a large mortality effect size doesn’t translate to a large cost-effectiveness estimate because GiveDirectly’s program is relatively expensive – costing ~$1,200 (nominal) per household – and untargeted – as not every household that receives a transfer has young children.”

- As mentioned above, we’re exploring a more targeted cash program to families at risk of losing children prematurely, which we expect would be much more cost effective under GiveWell’s model as their staff weighs preventing the death of a child under 5 highly (~50x more important than doubling someone’s consumption for a year).

We expect forthcoming research may further increase GiveWell’s assessment

GiveWell says this 3-4x update is “not the end of the story,” as they await two forthcoming studies (below) on our work, which could further increase their assessment. GiveWell says they “will be keeping a close eye on these developments, and (as always) will update our estimates in light of new information.”

1️) Spillovers: are they as powerful in poorer, more rural areas than western Kenya?

Researchers are studying the community-wide impacts of our program in Malawi, which GiveWell expects could shift their assumptions on “whether or not the non-inflationary spillovers generalize straightforwardly to another setting or whether they relied on specific features of the Western Kenyan economies” where the 2.5x study was conducted. As mentioned above, Egger et. al predict spillovers could be greater in poorer, more rural areas. We expect early-stage findings from Malawi in 2026.

GiveWell currently says they “find the arguments in favor of expecting smaller spillovers under more saturated programs in more remote contexts slightly more convincing, so we apply conservative downweights. However, these are speculative, and we think more direct evidence on the inflationary impacts of the Poverty Relief program in these contexts would allow us to make better-informed adjustments… an ongoing trial in Malawi may inform an update to this parameter in the future.”

2) Long-term impact: how sustained is the impact of one-time cash 5-7 years later?

Researchers surveyed Kenyan cash recipients 5-7 years after they received GiveDirectly cash and found they are still spending 12% more than the control group. They will release their findings in 2026.4

GiveWell, whose current consumption estimates 7 years after cash are ~3x smaller than these new results find, says they currently “don’t put much weight on these results because they haven’t been subjected to external scrutiny, and seem generally inconsistent with other experimental findings. However, if these results make it through academic peer review, we would probably update towards them.”

Below is a comparison of GiveWell’s assumptions and Egger et al.’s preliminary 5-7 year results, which if taken at face value would increase the cost-effectiveness of cash by another 1-2x under GiveWell’s current model:

We are excited to stay in conversation with GiveWell on our research and designs for cash programs even more cost-effective than our current one.

Any way you cut it, GiveDirectly is a cost-effective and scalable way to help people living in extreme poverty

Where you donate is ultimately up to you. As you consider, we’d like to emphasize direct giving’s large, untapped potential.

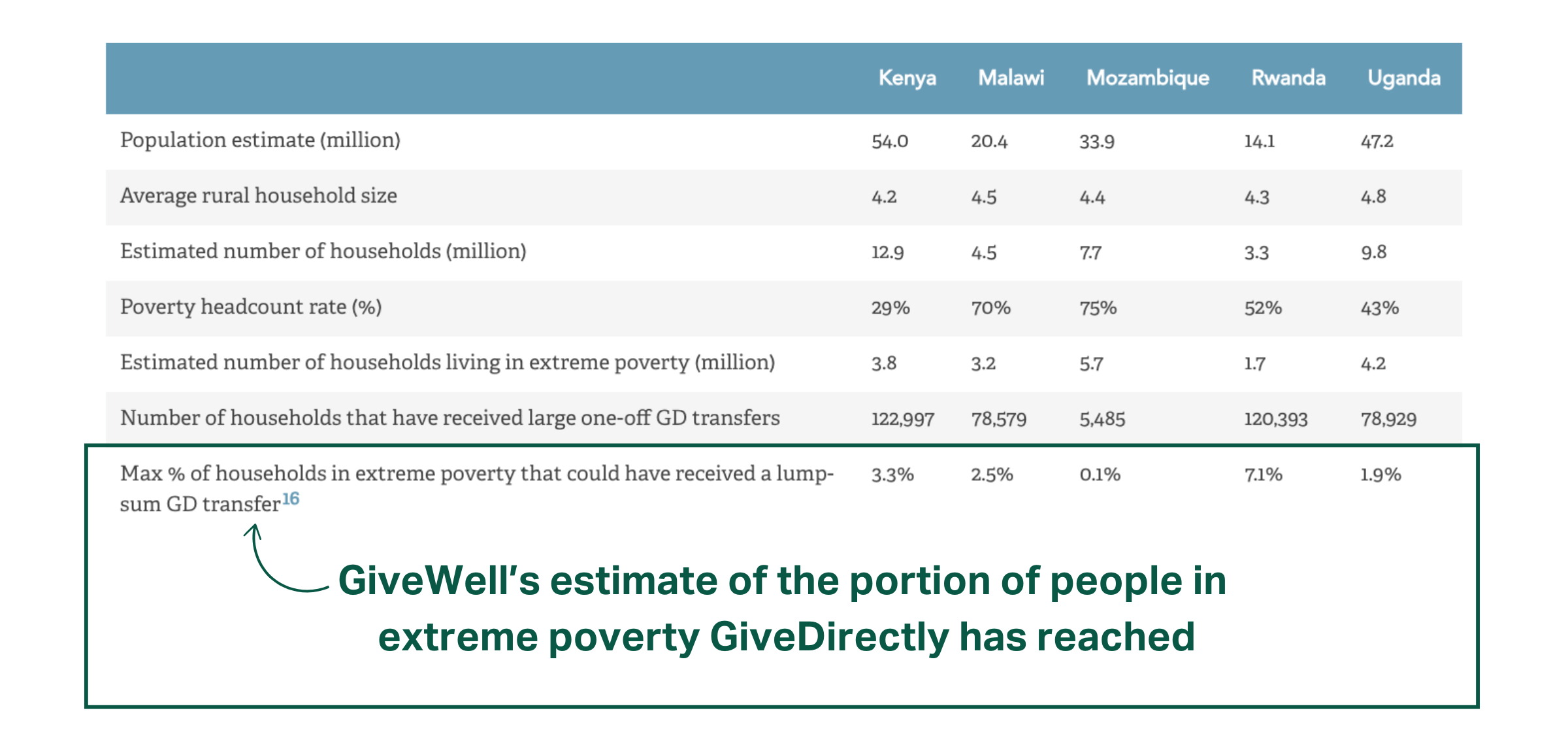

GiveWell’s assessment makes clear we have room for much more funding and could reach many more people in need: “the number of households GiveDirectly has reached with lump sum transfers… [is] significantly less than the number of households the World Bank estimates to be living in extreme poverty.“

We are well-positioned to reach millions more people in the countries we already work in. We estimate we could deliver ~$1.4B over the next 3 years – 450% more than we raised for our Africa programs in the last 3 years – while maintaining or exceeding our current operational quality (see Appendix).

We think this is possible because:

- 🌍 We’re set up for scale with the governments of the countries where we work.

- 💰 Between aid agencies and private wealth, there are billions available for fighting extreme poverty.

- 🌟 Despite biases against direct cash, we’re winning over influential hearts and minds.

When you give directly, you’re not only cost-effectively improving lives. You’re supporting work that is driving the $200 billion aid sector towards a cost-effective, scalable way to help the world’s poorest.

Appendicies

Appendix 1: estimating cost-effectiveness is nuanced, subjective, and important

GiveDirectly believes in rigorously measuring the impact of poverty interventions and are happy to see direct cash used as a benchmark to set the bar for others. The depth of GiveWell’s cash evaluation is possible because of the 7 independent randomized control trials of our Poverty Relief programs – a rarity for charities.

As you can see from the above, using that evidence to calculate cost-effectiveness is not a simple task – it requires nuance and subjectivity. We’re grateful GiveWell engages so thoroughly with the evidence on our work and shares [their analysis publicly] for you to consider.

Ultimately, you might draw different conclusions on the impact of direct cash based on how you weigh these research studies and what you believe are the most important outcomes (e.g., your own ‘moral weights’).

At GiveDirectly, we prioritize the preferences of the recipients –– giving directly lets them choose what they think is best, responding to their diverse values and priorities. We believe primarily evaluating the effects of direct cash on improvements to consumption and health may undervalue the full, diverse scope of the impact on people’s lives like boosts to psychological well-being or multi-generational education benefits.

Appendix 2: with more funding we could deliver ~$1.4B to people in extreme poverty by 2027

We’ve reached <4% of people living in extreme poverty in the countries we already work in

GiveWell’s chart below shows that even in countries where we’ve made meaningful progress, the remaining need is immense. In Rwanda alone, we’ve reached just ~130K people in poverty while 6M+ live on less than $2.15/day PPP.

We have the room for much more funding

This year, we expect to deliver ~$84M to Africans in poverty based on current funding, but we could have delivered up to $140M with the team we currently have.

Over the next 3 years (2025-2027), we could scale to deliver ~$1.4B with additional investment in central functions (tech, HR, programs management, safeguarding, internal audit) and in-country delivery costs, and while maintaining or exceeding efficiency targets.

Footnotes

- These preliminary results were published as a working paper in 2019, but GiveWell did not consider them until this assessment.

- Researchers found an average price inflation of just 0.1% adding, “even during periods with the largest transfers, estimated price effects are <1%.”

- Ugandan men who received $380 in 2008 had 22% higher incomes in 2020 than a control group. Fiala et al 2023

- The same researchers are currently conducting a 10-year follow-up of these recipients Kenya, which will shed further light on long-term impacts of cash, both directly, and the spillovers on non-recipients through longer-term changes in the structure of the local economy.