Summary of findings 2 years in:

- A monthly universal basic income (UBI) empowered recipients and did not create idleness. They invested, became more entrepreneurial, and earned more. The common concern of “laziness” never materialized, as recipients did not work less nor drink more.

- Both a large lump sum and a long-term UBI proved highly effective. The lump sum enabled big investments and the guarantee of 12 years of UBI encouraged savings and risk-taking.

- A short-term UBI was the least impactful of the designs but still effective. On nearly all important economic measures, a 2-year-only UBI performed less well than giving cash as a large lump sum or guaranteeing a long-term UBI, despite each group having received roughly the same total amount of money at this point. However, it still had a positive impact on most measures.

- Governments should consider changing how they deliver cash aid. Short-term monthly payments, which this study found to be the least impactful design, are the most common way people in both low- and high-income countries receive cash assistance, and it’s how most UBI pilots are currently designed.

Here’s a 3 minute audio summary of the findings from NPR:

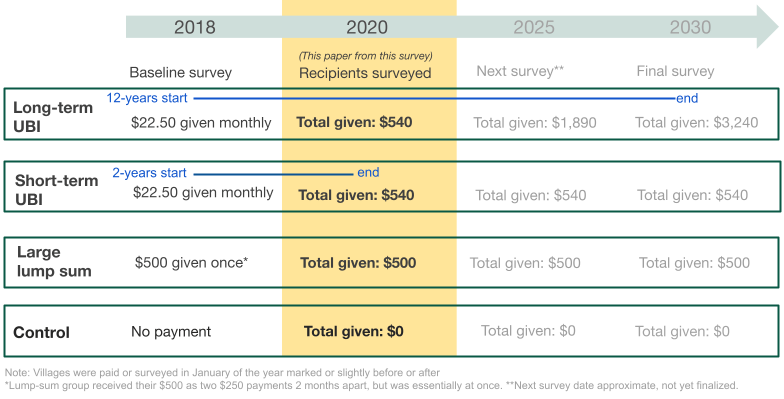

To learn about the most effective ways of delivering cash aid, GiveDirectly worked with a team of researchers to compare three ways of giving out funds.1 About 200 Kenyan villages were assigned to one of three groups and started receiving payment in 2018.

Now we have results 2 years in. These newly-released findings look at just the first two years (2018-2020), when all three groups had received roughly the same amount of money.

- Long-term UBI: a 12-year basic income of $22.50/month ($540 total after 2 years) with a commitment for 10 more years still to follow

- Short-term UBI: a 2-year basic income of $22.50/month, ($540 total after 2 years) with no more to follow

- Large lump-sum: one-off $500 payment given 2 years ago, with no more to follow2

These amounts are significant for people living below the extreme poverty line, which in Kenya means surviving on less than $33 a month or $400 a year.3

Researchers compared outcomes of these villages to a control group of similar villages that did not receive cash. The results are summarized below. You can read a table of the results here and the full paper here→

A monthly UBI made people in poverty more productive, not less

Critics of universal basic income often fear monthly cash payments disincentivize work; however, this study in rural Kenya, like many studies of cash transfers before it, found evidence to the contrary for all groups.

Highlights from the research paper:

- UBI improved agency and income: “Overall there is no evidence of UBI promoting ‘laziness,’ but evidence of substantial effects on occupational choice… impacts on total household income are also positive and significant.”

- Cash transfers increased savings: “The effect on both household and enterprise savings are positive and mostly significant… The amount the households have in rotating savings and credit associations (ROSCAs) also goes up significantly…”

- Cash did not change hours worked, but recipients shifted to self-employment: “Treated households are not working less… there is significant reduction in hours of wage work, all of which comes from work in agriculture, and a slightly larger increase in hours of non-agricultural self-employed work, so there is no net effect on total household labor supply.”

- Cash did not increase drinking: “Respondents [receiving cash] reported seeing fewer of their neighbors drinking daily, and were less likely to perceive drinking as a problem.”

Giving $500 as a lump sum improved economic outcomes more than giving it out over 24 months

If we have limited funds to help a person living in extreme poverty, should we give it out all at once or split it up monthly? This study finds that, while both have a positive impact, giving someone ~$500 as a lump sum rather than a short-term UBI is more effective across most measures.2

These findings have global significance as all governments face such trade-offs on how best to spend limited budgets – for example, Kenya’s spending on all social services amounted to $93 per person last year.4

A large lump sum was better than a short-term UBI on most economic outcomes

Highlights from the research paper:

- Short-term UBI was less effective overall: “The short-term UBI transfers had noticeably smaller effects, despite having delivered the same amount of capital to date… [In] communities that received the same amount of money structured as short-term monthly payments… aggregate output grew significantly less.”

- Lump sum created more new businesses: “We see many fewer enterprises being created in the short-term UBI group compared to lump sum.”

- Lump sum had the biggest improvement on incomes: “The [total household income] effect of the lump sums is large – 50% of the control group income…”

A short-term UBI was better at increasing food variety and reducing depression

Highlights from the research paper:

- Short-term UBI created more diet diversity: “[For consumption], the only significant difference is that there is more food variety in the short-term UBI than in lump sum… [However,] the fact that the lump sum group can save at a high return from the beginning gives them a marked advantage in terms of long-term consumption.”

- Short-term UBI was better at reducing depression: “The fact that lump sum has the least positive effects on depression despite being the group that has the largest increment in earnings, may be consistent with the fact that getting a large one-time payment is stressful (‘what happens if we waste the money’)… It also could be because both the long-term and short-term UBI arms have received payments in the last month [before the survey], unlike the lump sum.”

These results broadly align with two previous GiveDirectly studies (2016 & 2020) comparing one-time payments to short-term monthly ones. Another GiveDirectly study found most recipients also preferred receiving cash as a lump sum to short-term monthly payments (2023).

The promise of a long-term UBI encouraged saving and investment

If you knew you’d receive 12 years of a basic income rather than just 2 years, would you spend the first 2 years of money differently? These recipients certainly did.

Despite getting the same amount of money in these first 24 months ($540), those who knew they were getting a 12-year UBI improved more than those getting just a 2-year UBI on nearly every measure — probably because the long payment horizon allowed them to plan and save.

Highlights from the research paper:

- Long-term UBI encouraged saving: “Supporting … our theory that… the long-term UBI recipients behave differently from the short-term UBI because they find it worthwhile to save up for a bigger project, we see enormously higher rotating savings and credit association (ROSCA) participation from the long-term UBI group compared to the lump sum (who don’t need to save as much) and short-term UBI (who may not want to save).”

- Long-term UBI encouraged investments: “These results seem to be consistent with a simple model where… long-term UBI households have a greater incentive to invest… even when they have exactly the same income streams as the short-term UBI (the first two years) because they have a longer stream of high incomes to invest in the future.”

This research should inform how cash is given to people in extreme poverty

This study found a short-term UBI was the least impactful way to improve most outcomes other than in food variety. Yet short-term, small monthly payments are the most common way people in low-income countries receive cash transfers.

While short-term monthly cash is useful for emergency relief or for supporting basic needs during critical periods (e.g., early childhood), policymakers wanting to reduce poverty by creating wealth and independence should rethink using this popular design, as both a long-term UBI and a large lump sum were found to be significantly more transformative.5

To quote the researchers: “Tranching matters. Discussions about UBI usually begin from a narrative of meeting basic needs. But even the most destitute households often look for ways to accumulate sums of money large enough to make larger, lumpier purchases. Designing [cash] schemes in ways that respond to this need could make them a more compelling strategy for addressing extreme poverty over time.”

To put a finer point on it: [The researchers say] the findings thus far already have potential implications for policy. For instance, at present, “a lot of cash transfers that the World Bank runs in poor countries tend to be of the monthly-for-two-years kind of style.” And this new data adds substantial evidence to the view that, in fact, “the short-term [parceled out aid] is probably not such a smart policy. Because you could take the money and give it in a lump sum and get much bigger effects.”

NPR, 2023

Future results from this study will answer additional questions

Researchers aim to survey study participants again at 7 and 12 years, which will clarify if the benefit of a long-term UBI surpasses that of the one-time $500 and by how much. Ultimately, the long-term UBI group will receive about 6x as much money by the end, and it’s important to determine if the impact they achieve with this additional money is commensurate with the cost.

Quoting the researchers: “[Future surveys] will also reveal whether more generally the trajectories of households in the long-term UBI communities diverge from those in the others as they continue to receive transfers. The long horizon of their transfers may allow them to bide their time, waiting for the right opportunities to arrive. Or it may prove that the initial wealth transfer in the lump sum arm was sufficient to kickstart those communities onto permanently better trajectories at much lower cost than the long-term UBI approach.”

More research is needed in high-income countries

Similarly, most people who receive cash aid in high-income countries receive a small amount for a short period – e.g. most Americans only remain on public benefit programs for ≤1.5 years and nearly all guaranteed income pilots last ≤2 years.6

Results from rural Kenya are not necessarily applicable to high-income countries. However, there are nearly no similar randomized controlled trial findings of a long-term guaranteed income or a significantly large lump sum in countries like the U.S. While much more expensive in high-income countries, long-term income and large lump sum pilots should be tried and studied to learn if there are better ways to deliver cash that help people build wealth and escape poverty.

Study design and results

In this study, we define a UBI as:

- universal – given to every adult in a geography, in this case a village

- basic – sized so they can meet their most basic needs

- income – giving small, regular payments for over 1+ year.

For the Kenyan villages in this study, about half of residents were living below the extreme poverty line.

Note: the table below highlights the main results from the study, but the researchers evaluated many other outcomes. For the full set, please consult the full paper here→

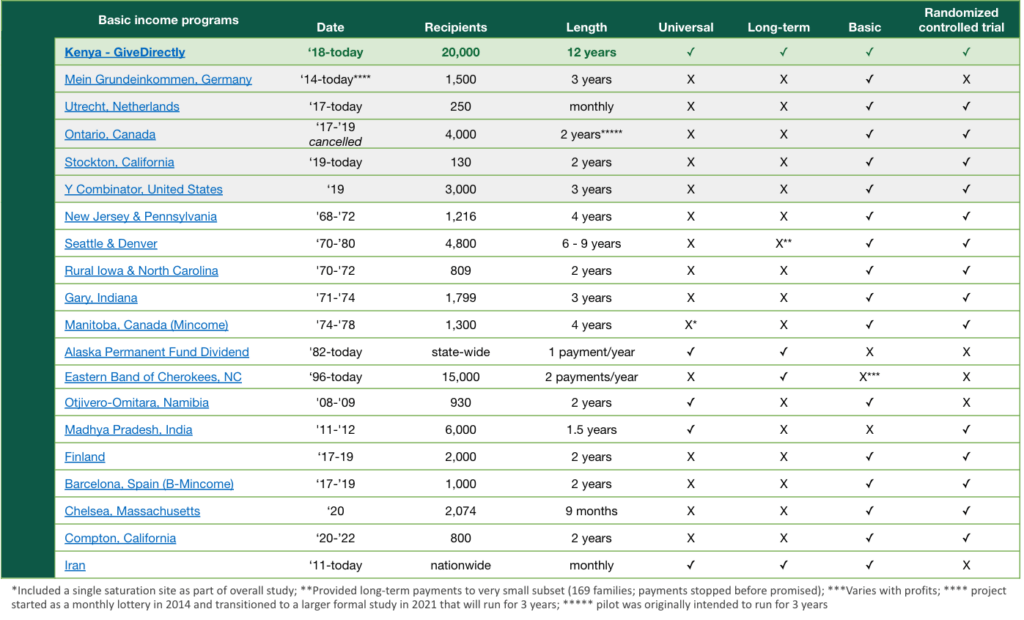

The chart below compares other prominent cash transfer programs/studies to this one

Footnotes

- Research team is led by Tavneet Suri (MIT Sloan) and joined by Nobel Prize winner Abhijit Banerjee (MIT), Alan Krueger (Princeton), Paul Niehaus (UCSD), and Michael Faye. Note: While Niehaus and Faye are GiveDirectly co-founders and board members, this research study is fully independent from GiveDirectly’s operations. Also noting that Alan Krueger passed away in 2019. We’ve also worked with researchers to measure what cadence and frequency of payment people in poverty prefer.

- The $22.50/month comes from the cost of meeting basic food needs in these rural counties. The $500 lump sum value was set by discounting the 2-year UBI total ($540) slightly to maintain a constant net present value. The lump-sum group received their $500 as two $250 payments 2 months apart. A Kenyan living below the extreme poverty line survives on<$400 a year, so you can imagine a $500 transfer as similar to someone getting an entire annual salary at once.

- The World Bank calculates the extreme poverty line based on a $2.15/day in purchasing power parity dollars. Factoring in local cost of living conversion and inflation, the extreme poverty line in Kenya is approximately $1.04/day in current USD.

- In 2022/23, the Kenyan Government allocated Ksh.766.3 billion to social sector investment (health, education, social protection, and water and sanitation) and has a population of 54 million people.

- Policymakers may choose large lump sum or long-term monthly payments depending on the community, policy goals, and budget.

- Some in the U.S. now advocate for large lump sums or a hybrid approach.