If you’re interested in supporting our work with refugees, you can do so here.

If you’re a long-term refugee from the Democratic Republic of Congo now living in Uganda, what is your biggest priority? It’s possible you have a skill-set that you could use to start a business but lack the capital. You might need equipment to farm land granted to you by the Ugandan government. You might be trying to get your children to school. Refugees, like all of the populations we work with, have highly diverse needs and goals, while operating under some of the most severe constraints.

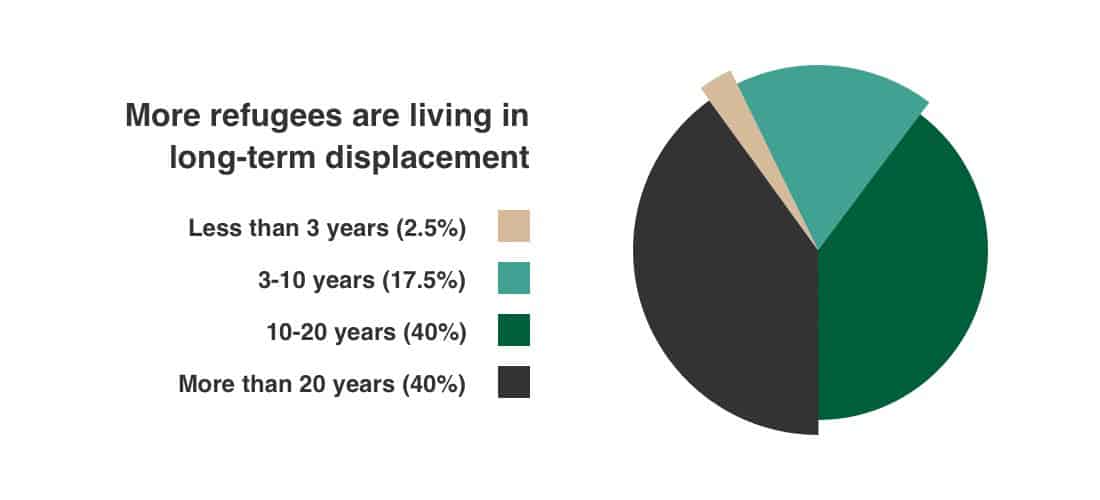

Against the backdrop of the worst global refugee crisis since WWII and a humanitarian system straining to respond to more refugees living in long-term displacement, we decided to deliver large cash transfers to families and challenge the status quo of subsistence aid.

In partnership with the IKEA Foundation, UK’s Department for International Development, Comic Relief, UBS Optimus Foundation, Vitol Foundation and the Tent Partnership for Refugees, we transferred $660 to 4,371 refugee and host households in Uganda, with the goal of empowering them to rebuild and reconstruct their own lives. We share some of what we learned below, with the full report here. The second phase, due to begin in early 2019, will deliver the program at scale with a rigorous, external evaluation of impact.

Why Uganda?

More progressive policies. We chose to work in Uganda, home to the largest refugee population in Africa, over a million people, and some of the world’s more progressive policies towards refugees. Here, refugees can work, set up businesses, and farm their own plots of land. In short, Uganda provides a great opportunity to test the impact of large, unconditional cash transfers in an environment where refugees have relative freedom to invest.

What was new about our approach?

Wealth transfers, not subsistence support. For those refugees who receive cash today, transfers are small, sized only to match a survival food ration. By design, they provide recipients with little opportunity to save or invest, only to meet their most immediate needs. In our pilot, each household received a transfer of ~660 USD, roughly equivalent to a year of World Food Programme rations: a significant sum, but within the scope of the existing humanitarian system.

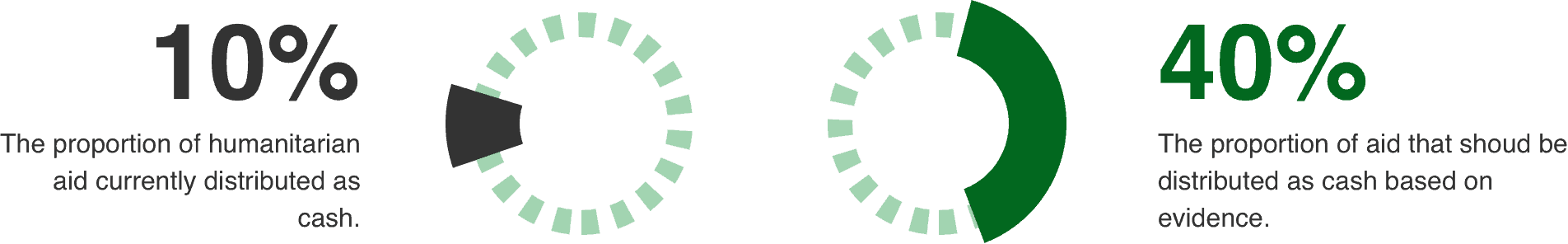

Unconditional cash, with no restrictions on recipients’ spending. For many refugees across the world, cash is delivered as vouchers, restricting spending to certain vendors and goods. These have been shown to be both less efficient and less effective than unrestricted cash. Despite extensive evidence on their efficacy across diverse humanitarian settings, cash-based approaches remain dwarfed by ‘in-kind’ ones, representing just 10% of humanitarian aid. In fact, if cash transfers were the default-mode for humanitarian assistance, research suggests that their share of the humanitarian budget would be roughly four-times bigger.

Supporting local, ‘host’ national communities, not just refugees. Around half of our recipients in the first phase of the pilot were families in the local host community. Also living in extreme poverty, they are often overlooked by aid organizations: just 1% of our host recipients reported having received any aid prior to GiveDirectly, a source of understandable tension between the two communities.

What did we learn?

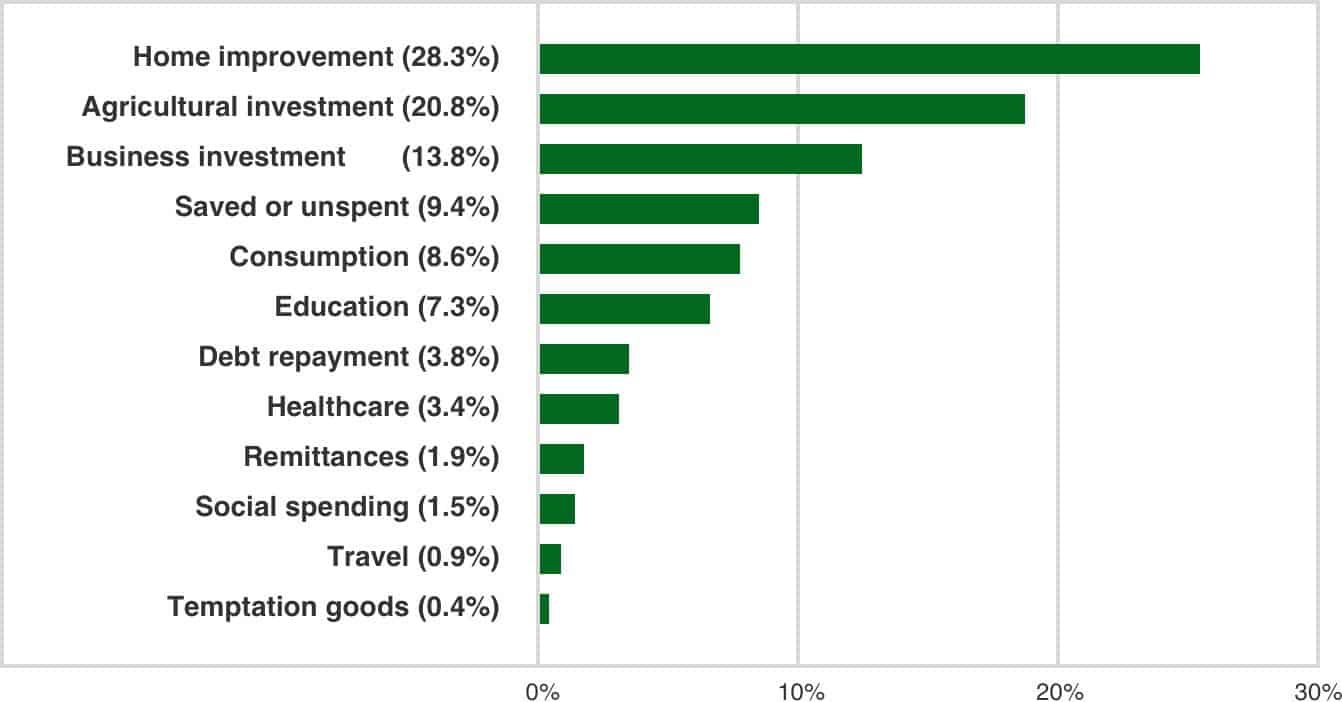

Choice rules. Cash transfers provide refugees, one of the most constrained populations in the world, with a unique degree of choice. Not surprisingly, recipients overwhelmingly prefered cash transfers to in-kind assistance. The flexibility of cash allowed them to allocate their resources according to their own needs, and those needs varied meaningfully. We can broadly bucket their spending into two categories, with around a quarter of the transfer value used to cover immediate necessities, such as food, clothing and paying off debts; and the remaining three quarters going to longer-term investments, such as housing, livestock, and businesses, or to the next generation, through education.

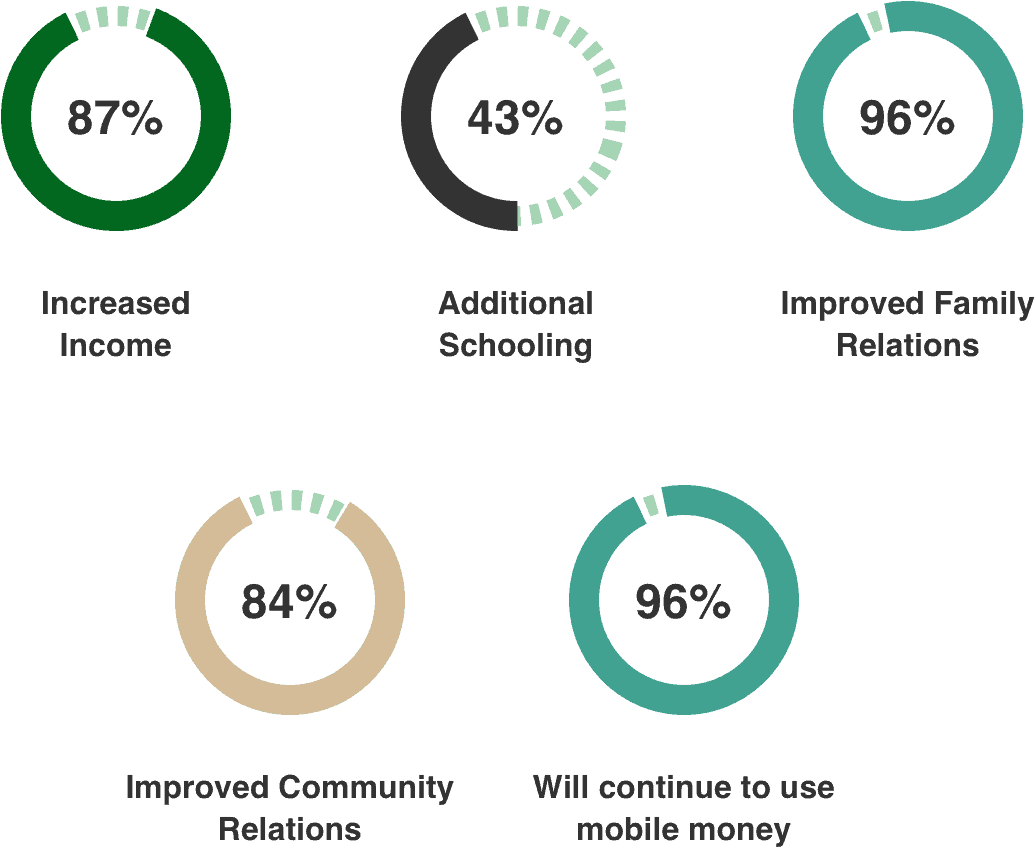

Recipients reported considerable and wide-ranging positive impact, soon after receiving and spending their transfers, including increased incomes, greater access to education, improved family and community relations and sustained financial inclusion.

The importance of flexibility was perhaps most starkly illustrated through an unexpected economic shock experienced by this population. Just prior to receiving their transfers, refugees had their farmland repossessed by the Ugandan government in order to house new arrivals. The proportion of the refugee population engaged in subsistence farming fell from 80% to 11%, while the share engaged in commercial farming fell from 26% to 5%. Essentially overnight, households lost their primary, often only, source of income and food. The transfers, however, allowed them to respond: continuing to meet their family’s daily needs, and for some, rapidly diversifying their sources of income. Prior to the program, 24% of refugee households owned a non-agricultural business; after the program, 55% did.

Payments arrived and markets responded. In addition to the diversity of needs and spending patterns, we learned that the delivery of large cash transfers to refugees is eminently feasible. Payments were sent digitally, through mobile money and a bank, and recipients safely received them (losses to theft and other adverse events was just 0.15% of total transfer size.) And markets responded, with more goods available at a greater number of shops. There was some evidence of price rises, though comparable studies suggest these were likely localized and short-term.

What’s next?

We plan to build on directional results from the pilot with a larger and more rigorous experiment. In doing so, we hope to inform some of the biggest challenges facing humanitarian aid today, from how best we can support refugees’ self-sufficiency, to how in time we can reduce the burden of the global millions reliant today on perpetual humanitarian support.