How big are villages in Malawi? The answer, our team has been learning, is not entirely straightforward. But it matters, for two key reasons: First, the randomized control trial we are running in partnership with USAID requires us to achieve a certain sample size (i.e. number of villages), within a budget constraint. If villages are the wrong size, we risk either overspending or being statistically underpowered. Second, if the boundaries aren’t clearly established, we risk sending money to designated “control” areas (i.e. those villages that are meant to serve as non-cash-receiving points of comparison).

As it turns out, there is no centralized database reporting the location and population of villages in Malawi. We have access to a few surveys conducted by NGOs and government sub-departments, but they are piecemeal and often unreliable. So, when we were kicking off operations, the job fell to our team to establish a robust estimate of village boundaries and size.

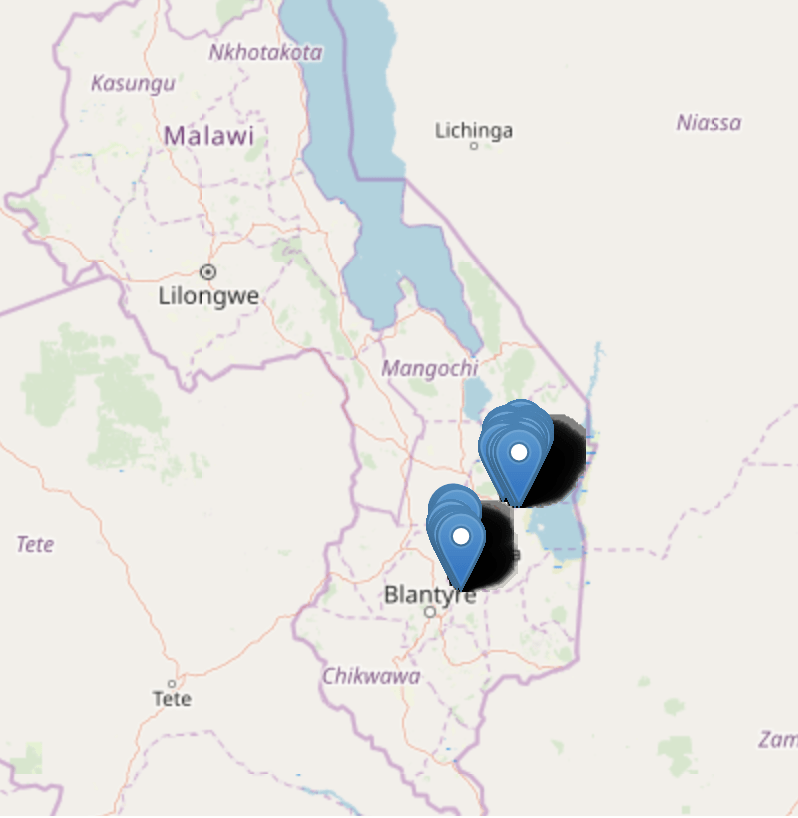

Starting in February, our team (29 field officers, working over 4.5 weeks) embarked on mapping 11 traditional authorities. The process, as is always the case, started with engaging the appropriate chain of command in local government: District Commissions, followed by Traditional Authorities, Group Village Headman, and finally Chiefs. We used available data from the Ministry of Water and the government’s own cash transfer program to zero in on villages listed as under 100 households.

Upon arrival in a given village, our teams visited every existing structure, collecting GPS coordinates and marking whether households were polygamous, child-headed (i.e. led by a minor), or vacant. Owing to the rainy season we saw a fair number of people whose homes had been washed away squatting temporarily in structures, which made assessing residency particularly difficult. Beyond that complication, we learned that the concept of geographic boundaries was often not relevant to communities – rather, they defined residence in relation to the Chief they paid allegiance to. Other unexpected challenges? One of our staff members had to ford a river to reach a village due to recent flooding (see photo below). In another case, a village was located adjacent to a national park, which left some of our field officers very worried about elephant encounters.

Once we’d constructed a full dataset across 403 villages, we authenticated it in two ways: First, any village that deviated by more than 25% from the the government estimate was flagged for another visit by our team. Second, every village was visualized on our analytics platform and inspected for overlapping GPS coordinates. Any villages that showed ambiguous borders were flagged for a second visit. Of the group of villages revisited, we approved those that came in at < 10% variance against the original census data. As a last step, we shared GPS coordinates for cleared villages with our research counterparts, so that they could randomize each one into either a treatment or control category.

So – 403 village mappings later, we have narrowed it down to a sample of 300 that meets all of our operational, budgetary, and research criteria. We’ll be launching enrollment shortly, and look forward to keeping you posted.

—

This study is made possible by the generous support of Good Ventures, and the American people through USAID. The contents of this blog are the responsibility of GiveDirectly, and do not necessarily reflect the views of USAID or the United States Government.