- How much good we do for people in poverty is often determined by how much and for how long we give them cash, so we need to study which designs work the best.

- In the U.S., most guaranteed income pilots implement similar designs, revealing little about how much cash and for how long will have the greatest impact for low-income Americans.

- Our first U.S. study comparing different cash designs found no measurable differences, so we’re adapting the design of our next phase in order to learn more.

Giving cash directly to people in poverty is proven to help. Our research increasingly focuses on testing the impact of different cash designs by varying how much, how often, and when people receive cash.1 For example, a first-of-its-kind study found the impact of delivering the same amount of cash to Kenyans in poverty is significantly greater if given all at once rather than broken into monthly payments.

We’re now studying this in the U.S. as well, and below we share what we know so far.

Current U.S. guaranteed income research offers little on which program designs work best

U.S. cities, counties, and states have launched 150+ guaranteed income (GI) pilots in the past decade. The particulars of how much cash assistance low-income Americans receive and for how long are determined by administrators or legislators. Due to limited funding, widespread need, political pressure, and administrative constraints, they often design GI programs based on factors beyond what the research says will work best, like:

- maximizing reach, e.g. if you have $5M in funds to distribute, you may choose to give $500 to 10,000 constituents rather than $10,000 to 500.

- modeling past programs, e.g. if you have to justify your design decisions, it may be easier to just point to a dozen other cities that gave a $500 monthly guaranteed income with good results than forge your own path.

- getting funds out as quickly as possible, e.g. programs that require funds to be delivered within a fast time frame often don’t have the time needed to develop more novel or complex designs.

This has resulted in too much design uniformity to tell us much about which programs can have the greatest impact. We need more innovation and variation in GI program designs in order to learn what works best, so that in turn we can:

- do more good for recipients. If we give out the right amount of cash at the right time in the right portions, more Americans can escape poverty. If we get it wrong, the program could be less impactful, as may have been the case in our US COVID-19 program →

- nudge the government toward more effective social spending. Despite spending nearly $600 billion annually on public assistance programs, the U.S. continues to have persistently high rates of poverty. Clearly, we need a new approach to improve the effectiveness of the American social safety net.

Findings from a wave of recent U.S. studies underscore the importance of testing more novel designs in future pilots, and it’s why GiveDirectly is now launching a newly designed phase of its oldest U.S. GI program.

Our first U.S. study comparing cash designs found no measurable differences between groups, though both saw positive impacts

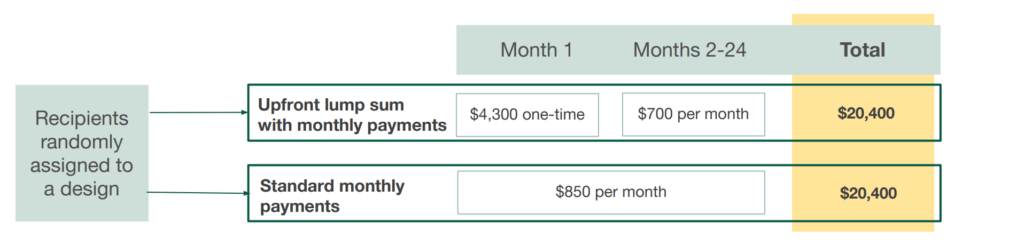

In 2022, GiveDirectly launched a guaranteed income program focused on Black women in Georgia called In Her Hands, in partnership with the Georgia Resilience and Opportunity Fund. The program compared two groups of recipients:

- Lump sum with monthly payments: half of recipients received an upfront $4,300 lump sum in the first month followed by $700 monthly payments for 23 months, totaling $20,400.

- Standard monthly payments: half of recipients received $850 monthly payments for all 24 months, totaling $20,400.

The idea to test the lump sum design came from community feedback suggesting that a large, upfront transfer could help recipients catch up on debt more quickly and pursue larger investment goals:

There may be a number of reasons we found no differences between design groups

Halfway through the two-year program, researchers found that recipients in both arms had less difficulty paying bills, fewer utility shutoffs, fewer evictions, more “rainy day” funds, and greater enrollment in higher education.2

However, there were no significant differences in outcomes observed between the two payment design groups. Interviews with recipients suggest this could be because:

- Lump sum was not large enough. Considering that the average debt burden of recipients at the start of the program was ~$35,500, the $4,300 upfront lump sum simply may not have been enough for them to get farther ahead than those receiving standard monthly payments.

- Recipients couldn’t choose their preferred design. Recipients were randomly assigned to one of the two payment groups. If they could have selected the design they believed would work best for them, there may have been a greater difference in outcomes. For example, recipients who wanted to invest or spend the upfront $4,300 could have self-selected for that design, while those in need of a higher income floor could have chosen the standard monthly payments design.

- Recipients couldn’t choose when to receive the lump sum. Lump sum recipients got the $4,300 in the first month, rather being offered a choice on when to receive it in the course of the two year program. There may be times when a lump sum is more useful (e.g. when tuition is due or when launching a business) and saving the first month’s windfall is difficult given weekly expenses.3

The data doesn’t tell us which factors mattered most, but these insights led us to hypothesize that giving recipients a larger lump sum (reason 1) and letting them choose their preferred design (reasons 2 and 3) could lead to greater impact.

In response, our next phase offers a larger, longer, recipient-choice-driven cash design

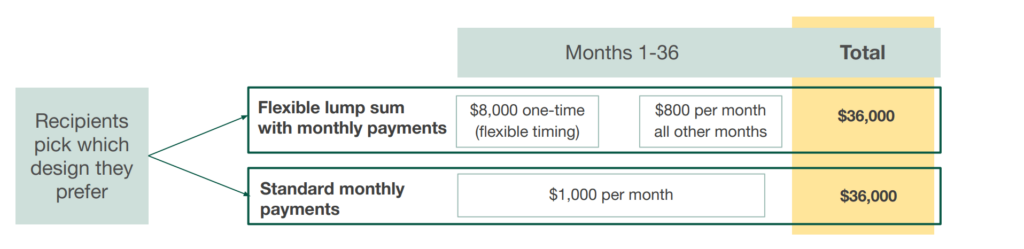

In July 2024, we expanded the program by enrolling 270 additional recipients in Georgia, with four key design changes based on lessons learned during the program’s first phase:

- Recipients choose the design they prefer. At enrollment, recipients were given the choice between the lump sum plus monthly payments or the standard monthly payments design based on what best fits their needs (reason 2).

- Lump sum is larger. Those in the lump sum group receive $8,000 rather than $4,300 (reason 1).

- Recipients choose when to receive their lump sum. Those who opt into the lump sum group are able to pick when they receive the $8,000 from a set of payout dates offered throughout the program (reason 3).

- Additional year of transfers. Recipients will receive a total of $36,000 over three years rather than $20,400 over two.4

To study the program’s impact, we’ve partnered with researchers at the Family Economic Policy Lab of Appalachian State University and the Social Policy Institute of Washington University in St. Louis to conduct both a randomized controlled trial and a qualitative interview study. One goal of the evaluation is to better understand recipient design preferences, answering key questions such as:

- What drives some recipients to choose standard monthly payments vs. a large lump sum with monthly payments?

- How do people use their funds differently depending on the payment design they select?

- When do people prefer to receive their lump sum payments? Do they prefer earlier in the program to finance large investments (as we see in Kenya) or at the end to create a financial cushion toward the program’s close?

This novel study could make billions in U.S. social spending more effective

Together, these design changes represent one of the largest total transfer amounts, largest lump sum amounts, and most flexible, recipient-driven GI programs in the U.S. Very few U.S. studies have evaluated such large transfer amounts. Notably, In Her Hands recipients will receive an average of $12,000 a year for three years, nearly equivalent to the U.S. Federal Poverty Line5, which aligns with what we’ve found works best in GiveDirectly’s Africa programs – providing cash roughly equal to a year’s consumption.

One of GiveDirectly’s key goals in the U.S. is to generate evidence from innovative programs like this one that can influence how both philanthropy and government tackle poverty and, ultimately, improve the social safety net for all Americans. We’re excited for what we learn next.

- GiveDirectly conducted a study in 2023 with past and present recipients in Kenya to understand recipient preferences around transfer design. ↩︎

- Outcomes in the 1-year research report compare recipients to those in a comparison group composed of eligible but non-selected program applicants. ↩︎

- There are a number of other possible reasons for the lack of observed differences between the two payment arms, including the possibility that the sample size was too small to detect more subtle differences that may have existed. The researchers also suggest that recipients were extremely savvy in applying their assigned treatment modality and pursued different strategies to reach similar outcomes (e.g. buying a car upfront with a lump sum or financing it with monthly payments). They also believe it is possible that we might see bigger differences emerge in the final year as recipients move closer to their personal goals. ↩︎

- The decision to extend the program from two to three years is linked to a key expansion goal around promoting longer-term wealth building for recipients. The increased duration also addresses a notable gap in the current research landscape, given that the majority of large-scale GI programs in the U.S. provide transfers for only two years or less. ↩︎

- The 2024 U.S. Federal Poverty Line is $15,060 per year for a household size of one. ↩︎