- Many U.S. studies show cash can have positive impacts, but some have found no impact or even negative impact

- Null results can have many causes, while negative results can help us design better programs in the future

- As U.S. cash research grows, we’ll know more about how best to deliver cash to Americans in need

Yolanda spent some of the monthly cash she receives through GiveDirectly’s program in Cook County, Illinois on a trip to the zoo with her grandson. “It felt good because that payment helps me be able to do those things,” she said. “So I don’t have to say to my grandson, ‘Oh, we can’t do that right now.’”

Nora in Georgia used some of her monthly GiveDirectly cash to move out of a mold-infested home. “This is such a miracle for me, and my kids,” she said. And Christopher said regarding our program with the City of Chicago: “It completely transformed my view of the government, not only in Chicago but nationally. It gave me an inkling of hope that things are happening.”

These are powerful anecdotal testaments to the power of giving cash to low-income Americans. However, there is not as much hard, quantitative evidence on the impact as there is from developing countries. Below we review what this preliminary evidence is finding – including some null and negative results – and share our thoughts on how U.S. cash research should evolve.

We do not expect all cash studies to be positive

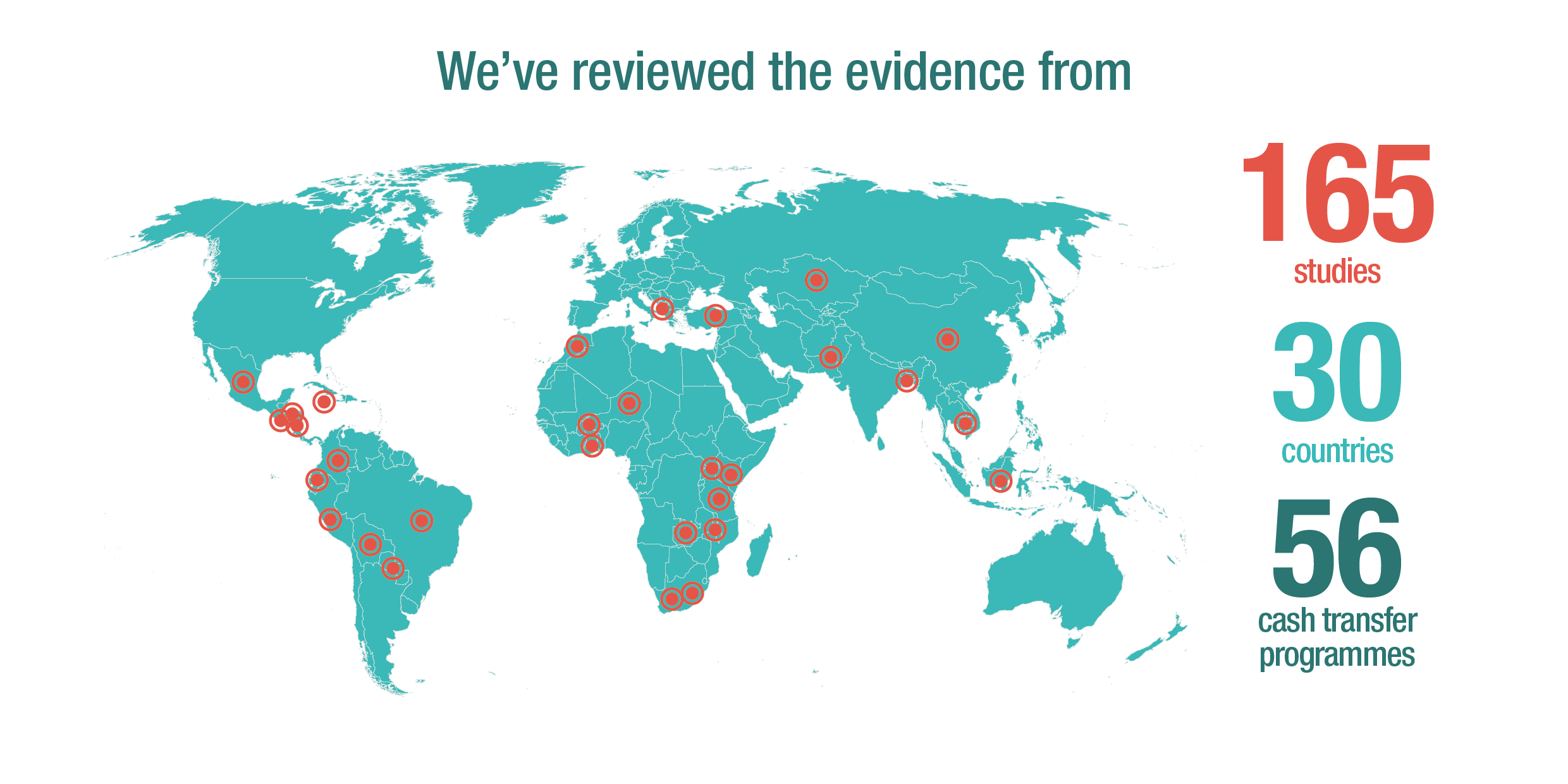

While there have been hundreds of randomized controlled trials studying the impact of direct cash, very few of these have taken place in the U.S. Most are from low- or low-middle-income countries like Kenya, where GiveDirectly started.

As we consider the nascent state of U.S. cash research, it’s worth remembering that global cash studies sometimes have null (no significant results) or even negative (significant worsening) findings.

This 2016 literature review of global cash programs found mostly positive impacts (blue bars in the chart below) across a variety of outcomes, especially monetary poverty, savings, and empowerment. But the review also found some studies had null results (gray bars) and a few had negative results (red bars):

This is all to say that direct cash is not a silver bullet, and it does not work equally well in every context. Research findings on cash in the U.S. tell a similar story.

Many U.S. studies show cash can have positive impacts

To date, we’ve seen promising evidence that cash in the U.S. can have positive impacts on income volatility, financial well-being, employment, homelessness, child development, health, and education.

- New findings indicate that receiving $1,000 of unconditional cash per month for three years can have several benefits for participants:

- Increased spending on basic needs, and on support for others

- Increased ability to pay for one’s own housing, and some participants reported that the cash helped them move out of toxic or abusive environments

- Higher likelihood to make budgets and plan for future education

- Increase in entrepreneurship, especially for recipients who identified as Black and/or female

- Less drug and alcohol abuse, especially for male participants.

- Increased use of formal medical services

- Studies on the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC) and the Child Tax Credit (CTC) showed that increases in tax refunds from these programs may have lowered rates of reported child maltreatment, reduced food insecurity or missed rent, and improved mental health.

- Children in American Indian households that received extra cash through Eastern Cherokee casino payments were more likely to graduate high school and were less likely to commit minor crimes as young adults.

- 2023 research from Vancouver, British Columbia suggests that recipients experiencing homelessness who received a large cash transfer spent fewer days in shelters or on the street and saved hundreds of dollars more than control participants.

- A recently published paper on the Baby’s First Years cash program found that mothers who received a higher cash transfer were more likely to read with their children and tell them stories than mothers who received a lower cash amount. The mothers who received more cash were also more likely to purchase books, toys, and clothing for their children.

- A 2022 study found that losing Supplemental Security Income (SSI) payments at age 18 significantly increased the likelihood that the former SSI recipient would be charged with a crime later in life.

Some U.S. cash studies have found no impact

- Our research on the impacts of a $1,000 transfer during the COVID-19 pandemic found that the transfers had little measurable effect on subjective well-being or material hardship.

- Another program responding to the COVID-19 pandemic gave Americans a one-time transfer of $500 or $2,000, and researchers found no evidence that more cash improved recipients’ financial or psychological well-being, cognitive capacity, or health.

- A study on cash received through Social Security benefits for families with infants in poor health found no impacts on long-term educational or earnings outcomes.

- The study on Baby’s First Years did not find a significant change in mothers’ happiness and optimism or in children’s time spent in childcare as a result of participating in the program.

- The Year 1 evaluation report of the Denver Basic Income Project, while finding some positive directional evidence on outcomes related to use of public services, housing, financial well-being, and leisure time, had mixed results when it came to mental and physical well-being.

- They also did not find any significant differences between their control and treatment groups, which makes it difficult to say whether the cash alone was responsible for positive outcomes.

- The aforementioned findings from OpenResearch included some null results on health outcomes:

- Improvements in mental health and food security were insignificant after the first year of the program

- No improvements to exercise, sleep, or other measures of physical health

- No improvements to self-reported access to health care

These null results can have many causes

Researchers for these U.S. studies offer a range of possible explanations for why cash does not always have a measurable impact:

- Cash transfer amounts may be too small in the U.S. context to move the needle on key outcomes

- Studying heterogeneous populations who have different goals and outcomes can yield inconsistent results

- Some studies may have insufficient statistical power to detect effects

- Survey challenges, like response bias or attrition

- High costs of conducting research over the course of a long-term study

More broadly, the flexibility of cash—one of its strengths—may also make it particularly difficult to study:

“Usually social intervention experimental studies evaluate interventions targeted at a very clear goal—does an educational program improve test scores? Does rental assistance improve housing security? Yet the flexibility of cash transfers allow recipients to allocate funds to a wide range of uses, and even spread a transfer over many different expenses…If beneficiaries spread their transfer over many different uses, this might mean we would not see an impact, and this poses a challenge, especially for untargeted, relatively small cash transfers.”

University of Michigan researchers

Negative results, while rare, are instructive in how to augment cash programs

Two studies that found cash in the U.S. can have a negative effect on recipients don’t necessarily indicate that cash is a harmful or ineffective tool for alleviating poverty. Rather, they point to the potential effectiveness that changes in program design can have.

A sampling of studies that found negative results provide important lessons for the design of cash transfer programs:

More broadly, one of the great attributes of cash – recipient choice – can itself fuel what researchers may frame as negative findings. For example, someone who receives unconditional cash may decide to work less (negative impact on employment and income) because they want to spend more time with their children. Another recipient may decide to forgo signing a lease (negative impact on housing) to pay down medical debt. However, it is not necessarily accurate to define these tradeoffs as negative outcomes.

Despite the contradictions inherent to social science research, we ultimately won’t know with certainty what combinations of cash plus other interventions work best to alleviate poverty in the U.S. without more research.

As U.S. cash research grows, we’ll know more about how best to deliver cash to Americans in need

This is an exciting time for research on direct cash in the U.S. with several major studies currently underway. At GiveDirectly, we’ve launched three new programs with ambitious research components:

- Rx Kids in Flint, Michigan, whose research will help us better understand the impacts of cash on mothers and babies

- In Her Hands in Georgia, an innovative program that centers recipient preference in its design, and whose research will provide insight into how a total of $36k in cash payments over three years impacts Black women experiencing poverty

- The Stability Investment for Family Housing, a state-funded program in Illinois, whose research will shed light on whether a large, one-time influx of cash ($9,500) can help families experiencing homelessness exit emergency shelter

These studies will add to the growing body of direct cash research in the U.S. by helping us identify if, when, how, and for whom cash is most effective. Unlike guaranteed income programs where thousands of diverse participants receive a relatively small amount of cash monthly, programs targeted toward specific demographic or geographic groups can reduce heterogeneous findings and may show that cash can be powerful in the U.S.

GiveDirectly will continue to deliver cash in the U.S., study cash against existing interventions, and prioritize recipient choice in the process

GiveDirectly delivers direct, unconditional cash because it upholds recipients’ dignity by allowing for flexibility, and the power and freedom of choice. We have found evidence to suggest that recipients prefer cash to in-kind assistance after disasters for these reasons, and recipients routinely elect to enroll in cash programs even after they consider how participation may negatively impact other benefits programs. We should trust their preferences.

We take limited null and negative research results (however they are defined) seriously. But we do not believe they are bellwethers for the end of cash in the U.S. These results will provide valuable insight into how we can better design future programs that avoid the pitfalls of previous efforts. It would be shortsighted to stop these efforts based on just a few null or negative findings.

GiveDirectly will also continue to deliver cash in the U.S. and study it against existing interventions. For example, there are fertile research opportunities in comparing direct cash against other non-cash government benefits through benchmarking studies. Rx Kids’ use of TANF funds and Illinois’ recent upswing in support for cash as a response to homelessness demonstrate that there is a political appetite for reassessing the effectiveness and bureaucratic efficiency of non-cash interventions.

Continuing to deliver cash and study its effects in the U.S. are vital steps toward better understanding how to end poverty in the world’s wealthiest country. We have much more to learn and more good to do for low-income Americans.